Social Structure

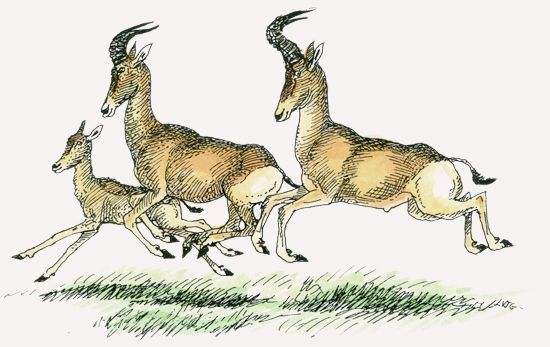

The only consistent bond among hartebeests is between mothers and their young, though this association weakens as more offspring are born. Female hartebeests assemble themselves into defined groups, though these units break apart and reform as females move about to find areas with the best grass and water sources, especially during the dry season. Males are territorial and compete fiercely to gain and defend areas they know females are most likely to visit. When a male holds a region, he becomes dominant over all other males that enter it. Only male hartebeests with a territory mate. Non-territorial males form bachelor herds of as many as 100 individuals.

Communication

Hartebeests communicate using a small number of vocalizations. Both calves and young adult males trying to show subordination to a dominant male emit a quack-like call. Hartebeests warn of predators using an alarm snort, varying the volume according to the level of danger. When a predator approaches, the hartebeest faces it directly, holding its head as high as possible, with its nose down and its ears pointed forward. Sometimes a hartebeest will follow the predator to keep it in sight. Even if a hartebeest doesn’t see the predator, it will spread the message that an enemy is near by picking up its neighbors’ alarm stance and snort.

Behavior

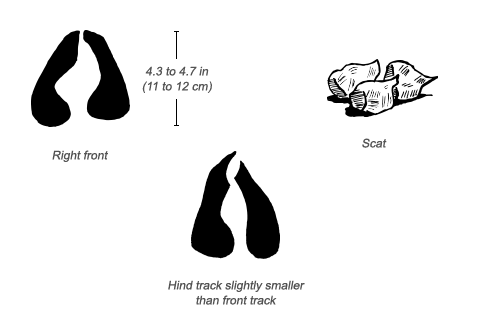

Like other ungulates, hartebeests alternate between resting, grazing, and ruminating from dawn until dusk. The actual pattern of activity for each of these behaviors varies slightly according to the subspecies as well as the season. (Scientists aren’t sure what hartebeests do at night.) Males are territorial and often fight to establish dominance and defend territories. Once a male successfully attains a territory, he scent-marks its boundaries by leaving piles of dung. Female hartebeests occasionally fight each other by clashing horns, mainly when they are competing for food or water.

Conservation

Because there has been little recognition of population distinctions among hartebeest subspecies, they are listed as being of lower risk by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) even though one species has gone extinct and three others are listed as endangered or critically endangered. The Laikipia hybrid is also endangered. Although there is no agreement on the reasons for its declining numbers, lion predation and changing habitat are suspected. The one notable exception to this declining trend is the red hartebeest in southern Africa. Its populations are actually increasing as a result of demand from the trophy-hunting industry.